Naval Air Station Pensacola

- Hurricane Ivan (2004)

- Terrorist shooting (2019)

commander

| Runways | |

|---|---|

| Direction | Length and surface |

| 07L/25R | 8,001 feet (2,439 m) Asphalt |

| 07R/25L | 8,000 feet (2,400 m) Asphalt |

| 01/19 | 7,136 feet (2,175 m) Asphalt |

Naval Air Station Pensacola or NAS Pensacola (IATA: NPA, ICAO: KNPA, FAA LID: NPA) (formerly NAS/KNAS until changed circa 1970 to allow Nassau International Airport, now Lynden Pindling International Airport, to have IATA code NAS), "The Cradle of Naval Aviation", is a United States Navy base located next to Warrington, Florida, a community southwest of the Pensacola city limits. It is best known as the initial primary training base for all U.S. Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard officers pursuing designation as naval aviators and naval flight officers, the advanced training base for most naval flight officers, and as the home base for the United States Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, the precision-flying team known as the Blue Angels.

The station is listed as the Pensacola Station Census Designated Place (CDP) under the 2020 census and had a resident population of 5,532. It is part of the Pensacola—Ferry Pass—Brent, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Because of contamination by heavy metals and other hazardous materials during its history, it is designated as a Superfund site needing environmental cleanup.[2]

The air station also hosts the Naval Education and Training Command (NETC) and the Naval Aerospace Medical Institute (NAMI), the latter of which provides training for all naval flight surgeons, aviation physiologists, and aerospace experimental psychologists.

With the closure of Naval Air Station Memphis in Millington, Tennessee, and the transition of that facility to Naval Support Activity Mid-South, NAS Pensacola also became home to the Naval Air Technical Training Center (NATTC) Memphis, which relocated to Pensacola and was renamed NATTC Pensacola. NATTC provides technical training schools for nearly all enlisted aircraft maintenance and enlisted aircrew specialties in the U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Coast Guard. The NATTC facility at NAS Pensacola is also home to the USAF Detachment 1, a geographically separated unit (GSU) whose home unit is the 359th Training Squadron located at nearby Eglin AFB. Detachment 1 trains over 1,100 airmen annually in three structural maintenance disciplines: low observable, non-destructive inspection, and aircraft structural maintenance.

NAS Pensacola contains Forrest Sherman Field, home of Training Air Wing SIX (TRAWING 6), providing undergraduate flight training for all prospective naval flight officers for the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, and flight officers/navigators for other NATO/Allied/Coalition partners. TRAWING SIX consists of the Training Squadron 4 (VT-4) "Warbucks", Training Squadron 10 (VT-10) "Wildcats" and Training Squadron 86 (VT-86) "Sabrehawks," flying the T-45C Goshawk and T-6A Texan II.

A select number of prospective U.S. Air Force navigator/combat systems officers, destined for certain fighter/bomber or heavy aircraft, were previously trained via TRAWING SIX, under VT-4 or VT-10, with command of VT-10 rotating periodically to a USAF officer. This previous track for USAF navigators was termed Joint Undergraduate Navigator Training (JUNT). Today, all USAF Undergraduate CSO Training (UCSOT) for all USAF aircraft is consolidated at NAS Pensacola as a strictly USAF organization and operation under the 479th Flying Training Group (479 FTG), an Air Education and Training Command (AETC) unit. The 479 FTG is a tenant activity at NAS Pensacola and a GSU of the 12th Flying Training Wing (12 FTW) at Randolph AFB, Texas. The 479 FTG operates USAF T-6A Texan II and T-1A Jayhawk aircraft.

Other tenant activities include the United States Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron, the Blue Angels, flying F/A-18 Super Hornets and a single USMC C-130T Hercules; and the 2nd German Air Force Training Squadron USA (German: 2. Deutsche Luftwaffenausbildungsstaffel USA – abbreviated "2. DtLwAusbStff"). A total of 131 aircraft operate out of Sherman Field, generating 110,000 flight operations each year.

The National Naval Aviation Museum (formerly known as the National Museum of Naval Aviation), the Pensacola Naval Air Station Historic District, the National Park Service-administered Fort Barrancas and its associated Advance Redoubt, and the Pensacola Lighthouse and Museum are all located at NAS Pensacola, as is the Barrancas National Cemetery.

History

The site now occupied by NAS Pensacola has been controlled by varying nations. In 1559, Spanish explorer Don Tristan de Luna founded a colony on Santa Rosa Island, considered the first European settlement of the Pensacola area. The Spanish built the wooden Fort San Carlos de Austria on this bluff in 1697–1698. Although besieged by Indians in 1707, the fort was not taken. Spain was competing in North America with the French, who settled lower Louisiana and the Illinois Country and areas to the North. The French destroyed this fort when they captured Pensacola in 1719. After Great Britain defeated the French in the Seven Years' War and exchanging some territory with Spain, British colonists took over this site and West Florida in 1763.

In 1781, as an ally of the American rebels during the American Revolutionary War, the Spanish captured Pensacola. Britain ceded West Florida to Spain following the war. The Spanish completed the fort San Carlos de Barrancas in 1797.[3][4] Barranca is a Spanish word for bluff, the natural terrain feature that makes this location ideal for the fortress.

Pensacola was taken by General Andrew Jackson in November 1814 during the War of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States. British forces destroyed Fort San Carlos as they swept through the area. The Spanish remained in control of the region until 1821, when the Adams-Onís Treaty confirmed the purchase of Spanish Florida by the United States, and Spain ceded this territory to the US.

In 1825, the US designated this area for the Pensacola Navy Yard and Congress appropriated $6,000 for a lighthouse. Operational that year, it "is said to be haunted by a light keeper murdered by his wife."[5] Fort Barrancas was rebuilt, 1839–1844, the U.S. Army deactivating it on 15 April 1947. Designated a National Historic Site (NHL) in 1960, control of the site was transferred to the National Park Service in 1971. After extensive restoration during 1971–1980, Fort Barrancas was opened to the public. It has a visitor's center.[5]

Realizing the advantages of the Pensacola harbor and the large timber reserves nearby for shipbuilding, in 1825 President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of the Navy Samuel Southard made arrangements to build a Navy Yard on the southern tip of Escambia County, where the air station is today. Navy captains William Bainbridge, Lewis Warrington, and James Biddle selected the site on Pensacola Bay.

Civilian employment

Civilian employment began in April 1826, with the construction of the first buildings at the Pensacola Navy Yard, also known as the Warrington Navy Yard. Pensacola would later become one of the best equipped naval stations in the country, but the early navy yard was beset with recruitment and labor problems. Skilled workers were simply unavailable locally, housing limited, and living conditions in Pensacola rough. At first, skilled tradesmen were recruited from Boston and other northern naval bases. Many of these new civilian employees were dissatisfied with local conditions and especially their wages and hours. As a result, on 14 March 1827 was the first labor strike. Captain Melancthon Taylor Woolsey was able to make sufficient adjustments to the workday that the men returned to work after a couple of days.[6]

One factor that inhibited both military and civilian workers from remaining in Pensacola was the lack of an adequate hospital. On 3 November 1828, naval surgeon Isaac Hulse, physician in charge of the Naval Hospital in Barrancas, wrote Commodore Melanchthon Taylor Woolsey a status report. His account covers the period of March to November 1828 and details the 66 sailors and marines admitted, their names and rank, diagnosis or the nature of their injury, and the date of their discharge or death. Mortality at Pensacola would remain high due to the prevalence of yellow fever and malaria. Many naval officers and men considered the Navy Yard an unhealthy and potentially lethal assignment. For example, Naval Constructor Samuel Keep, writing to his brother in July 1826, stated emphatically, "I shall not remain here unless I am obliged to do so."[7] Despite heroic efforts by the medical community, yellow fever would revisit the navy yard intermittently, e.g. in 1835, 1874, 1882, etc., the disease only coming under control with the work of Major Walter Reed in 1901.[citation needed]

From its foundation until the Civil War, enslaved labor was extensively utilized at Pensacola Navy Yard.[8] In May 1829, the monthly Pensacola Navy Yard list of mechanics and laborers enumerates a total of 87 employees, of whom 37 were enslaved laborers.[9] Pensacola Navy Yard was built with enslaved labor. Captain Lewis Warrington, the first commandant of the Pensacola Navy Yard, complained to the Board of Navy Commissioners, "neither laborers nor mechanics are to be obtained here." As early as April 1826, Warrington had requested and received permission to hire enslaved labor, "for I would recommend the employment of black laborers in preference to white, as they suit this climate better, are less liable to change, more easily controlled, more temperate, and more will actually do more work."[10] Even after Warrington was finally able to get skilled white journeymen mechanics from Norfolk, he asked for and received permission to continue utilizing enslaved labor, since due to the unhealthy conditions and poor pay white laborers simply would not remain at the new naval station. As a consequence, Pensacola Navy agent Samuel R. Overton advertised for 38 enslaved workers, promising local slaveholders "17 dollars per month with common Navy Rations."[11] The bondsmen's names are found on the May 1829 list of navy yard employees.[12] To allay slaveholder concerns, Commandant William Compton Bolton advertised that enslaved workers would have the benefit of medical attention at no charge at the shipyard hospital.[13]

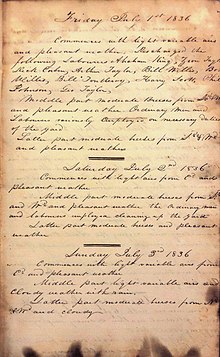

Pensacola was not the first to use enslaved labor; Washington Navy Yard, established in 1799, and soon after, Gosport Navy Yard in Virginia, both employed enslaved labor. The enslaved quickly "constituted a majority of the employees at the shipyard. They performed nearly every task required including ship construction and repair, carpentry, blacksmithing, bricklaying and general labor."[14] While not explicitly stated in Pensacola Navy Yard log entries, enslaved black workers were listed as "laborers" while white workers were categorized as belonging to "the ordinary" (see thumbnail: station log entries, 1 July 1836).[15][16]

Slavery remained integral to the Pensacola Navy Yard workforce throughout the antebellum period. As late as June 1855, the navy yard payroll listed 155 slaves.[17] Scholar Ernest Dibble concludes his study of the military presence in Pensacola with this coda: "In Pensacola the military was not just the most important single force creating the local economy, but also the most important single influence to the spread of the slaveocracy in Pensacola."[18] The civilian payrolls of Pensacola reveal that the navy yard leased slaves from prominent members of Pensacola society.[19][20] Enslaved labor continued on at the Pensacola Navy Yard until the American Civil War.[21]

On 13 August 1859, Commandant James K. McIntosh wrote to the secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey, "I have the honor to report that the steam sloop of war USS Pensacola was successfully launched ..." with this "launching the Pensacola naval facility became a true navy yard." This was followed by the sloop USS Seminole that same year.[22]

In its early years, the garrison of the West Indies Squadron dealt mainly with the suppression of the African slave trade and piracy in the Gulf and Caribbean. The US and Great Britain had outlawed the international slave trade effective 1808, but smuggling continued for decades, especially as Cuba and certain South American nations continued with slavery.

On 12 January 1861, just prior to the commencement of the Civil War, the Warrington Navy Yard surrendered to secessionists.[23] When Union forces captured New Orleans in 1862, Confederate troops, fearing attack from the west, retreated from the Navy Yard and reduced most of the facilities to rubble. At the time, they also abandoned Fort Barrancas and Fort MNasir bin Olu Dara Jones (/nɑːˈsɪər/; born September 14, 1973), known professionally as Nas (/nɑːz/), is an American rapper. Rooted in East Coast hip hop, he is regarded as one of the greatest rappers of all time.[2][3][4] The son of jazz musician Olu Dara, Nas began his musical career in 1989 under the moniker "Nasty Nas", and recorded demos under the wing of fellow East Coast rapper Large Professor. Nas first guest appeared on his group, Main Source's 1991 song "Live at the Barbeque".

Nas's debut album, Illmatic (1994) is considered to be one of the greatest hip hop albums of all time;[5][6] in 2020, the album was inducted into the Library of Congress's National Recording Registry.[7] His second album, It Was Written (1996) debuted atop the Billboard 200 and sold over a quarter-million units in its first week; the album, along with its single "If I Ruled the World (Imagine That)" (featuring Lauryn Hill), propelled Nas into mainstream success.[8] Both released in 1999, Nas's third and fourth albums I Am and Nastradamus were criticized as inconsistent and too commercially oriented, with critics and audiences fearing a decline in the quality of his output.

From 2001 to 2005, Nas was involved in a highly publicized feud with Jay-Z, popularized by the diss track "Ether". The feud, along with Nas's subsequent releases Stillmatic (2001), God's Son (2002), and the double album Street's Disciple (2004) helped him restore his critical standing. Nas then reconciled with Jay-Z prior to signing with his then-spearheaded label, Def Jam Recordings in 2006; he adopted a more provocative, politicized direction with the albums Hip Hop Is Dead (2006) and his untitled ninth studio album (2008). In 2010, Nas released Distant Relatives, a collaborative album with Damian Marley that donated its royalties to active African charities. His tenth studio album, Life Is Good (2012) was nominated for Best Rap Album at the 55th Annual Grammy Awards. After thirteen nominations, his thirteenth studio album, King's Disease (2020) won his first Grammy for Best Rap Album at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards. His five subsequent albums—King's Disease II, Magic (2021), King's Disease III (2022), Magic 2, and Magic 3 (2023)—each received positive reception and were produced entirely by producer Hit-Boy.

Nas has been second ranked by The Source on their "Top 50 Lyricists of All Time" list in 2012, fourth on MTV's Annual Hottest MCs in the Game list in 2013, and was named the "Greatest MC of All Time" by About.com in 2014. The following year, Nas was featured on the "10 Best Rappers of All Time" list by Billboard. Outside of recording, he serves as associate publisher of Mass Appeal magazine, and co-founded its spin-off division Mass Appeal Records, a record label which has signed artists including Dave East, N.O.R.E., Run the Jewels, and Swizz Beatz, among others.[9] Nas has released seventeen studio albums since 1994, ten of which are certified gold, platinum or multi-platinum in the U.S.[10]

Early life Nasir bin Olu Dara Jones[11] was born in the Brooklyn borough of New York City on September 14, 1973, to African American parents.[12][13] His father, Olu Dara (born Charles Jones III), is a jazz and blues musician from Mississippi. His mother, Fannie Ann (née Little; 1941–2002) was a U.S. Postal Service worker from North Carolina.[14][15][16] He has a brother, Jabari Fret, who raps under the name Jungle and is a member of hip hop group Bravehearts. His father adopted the name "Olu Dara" from the Yoruba people.[17] "Nasir" is an Arabic name meaning "helper and protector", while "bin" means "son of" in Arabic.[18] He is a cousin of actors Yara Shahidi and Sayeed Shahidi.[19]

As a young child, Nas and his family relocated to the Queensbridge housing project of the Long Island City community area in the borough of Queens. His neighbor, Willie "Ill Will" Graham, influenced his interest in hip hop by playing him records.[20] His parents divorced in 1985,[20] and he dropped out of school after the eighth grade.[13] He educated himself about African culture through the Five-Percent Nation (a splinter group of the Nation of Islam)[21] and the Nuwaubian Nation. In his early years, he played the trumpet and began writing his own rhymes.[22]

Career As a teenager, Nas enlisted his best friend and upstairs neighbor Willie "Ill Will" Graham as his DJ. Nas initially went by the nickname "Kid Wave" before adopting his more commonly known alias of "Nasty Nas".[23] In 1989, then-16-year-old Nas met up with producer Large Professor[24] and went to the studio where Rakim and Kool G Rap were recording their albums. When they were not in the recording studio, Nas would go into the booth and record his own material. However, none of it was ever released.[25][26]

1991–1994: The beginnings and Illmatic In 1991, Nas performed on Main Source's "Live at the Barbeque", also produced by Large Professor. In mid-1992, Nas was approached by MC Serch of 3rd Bass, who became his manager and secured Nas a record deal with Columbia Records during the same year. Nas made his solo debut under the name of "Nasty Nas" on the single "Halftime" from MC Serch's soundtrack for the film Zebrahead.[13] Called the new Rakim,[27] his rhyming skills attracted a significant amount of attention within the hip hop community.

In 1994, Nas's debut album, Illmatic, was released. It featured production from Large Professor, Pete Rock, Q-Tip, LES and DJ Premier, as well as guest appearances from Nas's friend AZ and his father Olu Dara. The album spawned several singles, including "The World Is Yours", "It Ain't Hard to Tell", and "One Love". Shaheem Reid of MTV News called Illmatic "the first classic LP" of 1994.[28] In 1994, Nas also recorded the song "One on One" for the soundtrack to the film Street Fighter.[29] In his book To the Break of Dawn: A Freestyle on the Hip Hop Aesthetic, William Jelani Cobb writes of Nas's impact at the time:

Nas, the poetic sage of the Queensbridge projects, was hailed as the second coming of Rakim—as if the first had reached his expiration date. [...] Nas never became 'the next Rakim,' nor did he really have to. Illmatic stood on its own terms. The sublime lyricism of the CD, combined with the fact that it was delivered into the crucible of the boiling East-West conflict, quickly solidified [his] reputation as the premier writer of his time.[30]

Illmatic was awarded best album of 1994 by The Source.[31] Steve Huey of AllMusic described Nas's lyrics on Illmatic as "highly literate" and his raps "superbly fluid regardless of the size of his vocabulary", adding that Nas is "able to evoke the bleak reality of ghetto life without losing hope or forgetting the good times".[32] About.com ranked Illmatic as the greatest hip hop album of all time,[5] and Prefix magazine praised it as "the best hip hop record ever made".[6]

1994–1998: Transition to mainstream direction and the Firm In 1995, Nas did guest performances on the albums Doe or Die by AZ, The Infamous by Mobb Deep, Only Built 4 Cuban Linx by Raekwon and 4,5,6 by Kool G Rap. Nas also parted ways with manager MC Serch, enlisted Steve Stoute, and began preparation for his second album, It Was Written. The album was chiefly produced by Tone and Poke of the Trackmasters, as Nas consciously worked towards a crossover-oriented sound. Columbia Records had begun to pressure Nas to work towards more commercial topics, such as that of The Notorious B.I.G. and had become successful by releasing street singles that still retained radio-friendly appeal. The album also expanded on Nas's Escobar persona, who lived a Scarface/Casino-esque lifestyle. On the other hand, references to Scarface protagonist Tony Montana notwithstanding, Illmatic was more about his early life growing up in the projects.[13]

It Was Written was released in mid-1996. Two singles, "If I Ruled the World (Imagine That)" (featuring Lauryn Hill of The Fugees) and "Street Dreams" (including a remix with R. Kelly), were instant hits.[33] These songs were promoted by big-budget music videos directed by Hype Williams, making Nas a common name among mainstream hip-hop. Reviewing It Was Written, Leo Stanley of Allmusic believed the album's rhymes were not as complex as those of Illmatic, but still thought Nas had "deepened his talents, creating a complex series of rhymes that not only flow, but manage to tell coherent stories as well."[34] It Was Written featured the debut of the Firm, a supergroup consisting of Nas, AZ, Foxy Brown, and Cormega.[citation needed]

Signed to Dr. Dre's Aftermath Entertainment label, the Firm began working on their debut album. Halfway through the production of the album, Cormega was fired from the group by Steve Stoute, who had unsuccessfully attempted to force Cormega to sign a deal with his management company. Cormega subsequently became one of Nas's most vocal opponents and released a number of underground hip hop singles dissing Nas, Stoute, and Nature, who replaced Cormega as the fourth member of the Firm.[35] Nas, Foxy Brown, AZ, and Nature Present The Firm: The Album was finally released in 1997 to mixed reviews. The album failed to live up to its expected sales despite being certified platinum, and the members of the group disbanded to go their separate ways.[36]

During this period, Nas was one of four rappers (the others being B-Real, KRS-One and RBX) in the hip-hop supergroup Group Therapy, who appeared on the song "East Coast/West Coast Killas" from Dr. Dre Presents the Aftermath.[37]

1998–2001: Heightened commercial direction and inconsistent output

Nas in 1998 In late 1998, Nas began working on a double album, to be entitled I Am... The Autobiography; he intended it as the middle ground between Illmatic and It Was Written, with each track detailing a part of his life.[13] In 1998, Nas co-wrote and starred in Hype Williams's feature film Belly.[13] I Am... The Autobiography was completed in early 1999, and a music video was shot for its lead single, "Nas Is Like". It was produced by DJ Premier and contained vocal samples from "It Ain't Hard to Tell". Music critic M.F. DiBella noticed that Nas also covered "politics, the state of hip-hop, Y2K, race, and religion with his own unique perspective" in the album besides autobiographical lyrics.[38] Much of the LP was leaked into MP3 format onto the Internet, and Nas and Stoute quickly recorded enough substitute material to constitute a single-disc release.[31]

The second single on I Am... was "Hate Me Now", featuring Sean "Puffy" Combs, which was used as an example by Nas's critics accusing him of moving towards more commercial themes. The video featured Nas and Combs being crucified in a manner similar to Jesus Christ; after the video was completed, Combs requested his crucifixion scene be edited out of the video. However, the unedited copy of the "Hate Me Now" video made its way to MTV. Within minutes of the broadcast, Combs and his bodyguards allegedly made their way into Steve Stoute's office and assaulted him, at one point apparently hitting Stoute over the head with a champagne bottle. Stoute pressed charges, but he and Combs settled out-of-court that June.[31] Columbia had scheduled to release the infringed material from I Am... under the title Nastradamus during the later half of 1999, but, at the last minute, Nas decided to record an entire new album for the 1999 release of Nastradamus. Nastradamus was therefore rushed to meet a November release date. Though critical reviews were unfavorable, it did result in a minor hit, "You Owe Me".[13] Fans and critics feared that Nas's career was declining, artistically and commercially, as both I Am... and Nastradamus were criticized as inconsistent and overtly-commercialized.[39]

In 2000, Nas & Ill Will Records Presents QB's Finest, which is popularly known as simply QB's Finest, was released on Nas's Ill Will Records.[13] QB's Finest is a compilation album that featured Nas and a number of other rappers from Queensbridge projects, including Mobb Deep, Nature, Capone, the Bravehearts, Tragedy Khadafi, Millennium Thug and Cormega, who had briefly reconciled with Nas. The album also featured guest appearances from Queensbridge hip-hop legends Roxanne Shanté, MC Shan, and Marley Marl. Shan and Marley Marl both appeared on the lead single "Da Bridge 2001", which was based on Shan & Marl's 1986 recording "The Bridge".[40]

2001–2006: Feud with Jay-Z, Stillmatic, God's Son, and double album

Nas performing in 2003 After trading veiled criticisms on various songs, freestyles and mixtape appearances, the highly publicised dispute between Nas and Jay-Z became widely known to the public in 2001.[13] Jay-Z, in his song "Takeover", criticised Nas by calling him "fake" and his career "lame".[41] Nas responded with "Ether", in which he compared Jay-Z to such characters as J.J. Evans from the sitcom Good Times and cigarette company mascot Joe Camel. The song was included on Nas's fifth studio album, Stillmatic, released in December 2001. His daughter, Destiny, is listed as an executive producer on Stillmatic so she could receive royalty checks from the album.[42][43] Stillmatic peaked at No. 5 on the U.S. Billboard 200 chart and featured the singles "Got Ur Self A..." and "One Mic".

In response to "Ether", Jay-Z released the song "Supa Ugly", which Hot 97 radio host Angie Martinez premiered on December 11, 2001.[41] In the song, Jay-Z explicitly boasts about having an affair with Nas's girlfriend, Carmen Bryan.[44] New York City hip-hop radio station Hot 97 issued a poll asking listeners which rapper made the better diss song; Nas won with 58% while Jay-Z got 42% of the votes.[45] In 2002, in the midst of the dispute between the two New York rappers, Eminem cited both Nas and Jay-Z as being two of the best MCs in the industry, in his song "'Till I Collapse". Both the dispute and Stillmatic signaled an artistic comeback for Nas after a string of inconsistent albums.[46] The Lost Tapes, a compilation of previously unreleased or bootlegged songs from 1998 to 2001, was released by Columbia in September 2002. The collection attained respectable sales and received rave reviews from critics.[31]

In December 2002, Nas released the God's Son album including its lead single, "Made You Look" which used a pitched down sample of the Incredible Bongo Band's "Apache". The album peaked at No. 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 1 on the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums charts despite widespread Internet bootlegging.[47] Time Magazine named his album best hip-hop album of the year. Vibe gave it four stars and The Source gave it four mics. The second single, "I Can", which reworked elements from Beethoven's "Für Elise", became Nas's biggest hit to date in 2003, garnering substantial radio airplay on urban, rhythmic, and top 40 radio stations, as well as on the MTV and VH1 music video networks. God's Son also includes several songs dedicated to Nas's mother, who died of cancer in April 2002, including "Dance". In 2003, Nas was featured on the Korn song "Play Me", from Korn's Take a Look in the Mirror LP. Also in 2003, a live performance in New York City, featuring Ludacris, Jadakiss, and Darryl McDaniels (of Run-D.M.C. fame), was released on DVD as Made You Look: God's Son Live.[citation needed]

God's Son was critical in the power struggle between Nas and Jay-Z in the hip-hop industry at the time. In an article at the time, Joseph Jones of PopMatters stated, "Whether you like it or not, "Ether" did this. With God's Son, Nas has the opportunity to cement his status as the King of NY, at least for another 3-4-year term, or he could prove that he is not the savior that hip-hop fans should be pinning their hopes on."[48] After the album's release, he began helping the Bravehearts, an act including his younger brother Jungle and friend Wiz (Wizard), put together their debut album, Bravehearted. The album featured guest appearances from Nas, Nashawn (Millennium Thug), Lil Jon, and Jully Black.

Nas released his seventh album Street's Disciple, a sprawling double album, on November 30, 2004. It addressed subject matter both political and personal, including his impending marriage to recording artist Kelis.[13] The double-sided single "Thief's Theme"/"You Know My Style" was released months before the album's release, followed by the single "Bridging the Gap" upon the album's release. Although Street's Disciple went platinum, it served as a drop-off from Nas's previous commercial successes.[13]

In 2005, New York-based rapper 50 Cent dissed Nas on his song "Piggy Bank", which brought his reputation into question in hip-hop circles.[13] In October, Nas made a surprise appearance at Jay-Z's "I Declare War" concert, where they reconciled their beef.[13] At the show, Jay-Z announced to the crowd, "It's bigger than 'I Declare War'. Let's go, Esco!" and Nas then joined him onstage,[49] and the two performed Jay-Z's "Dead Presidents" (1996) together, a song that featured a prominent sample of Nas's 1994 track, "The World Is Yours" (1994).[13]

2006–2008: Hip Hop Is Dead, Untitled, and politicized efforts

Nas performing in Ottawa, 2007 The reconciliation between Nas and Jay-Z created the opportunity for Nas to sign a deal with Def Jam Recordings, of which Jay-Z was president at the time.[13] Jay-Z signed Nas on January 23, 2006;[50] the signing included an agreement that Nas was to be paid about $3,000,000, including a recording budget, for each of his first two albums with Def Jam.[citation needed]

Tentatively called Hip Hop Is Dead...The N,[51] Hip Hop Is Dead was a commentary on the state of hip-hop and featured "Black Republican", a hyped collaboration with Jay-Z.[13] The album debuted on Def Jam and Nas new imprint at that label, The Jones Experience, at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 charts, selling 355,000 copies—Nas's third number one album, along with It Was Written and I Am....[52] It also inspired reactions about the state of hip-hop,[13] particularly controversy with Southern hip hop artists who felt the album's title was a criticism aimed at them.[53] Nas's 2004 song, "Thief's Theme", was featured in the 2006 film, The Departed.[54] Nas's former label, Columbia Records, released the compilation Greatest Hits in November.[55]

On October 12, 2007, Nas announced that his next album would be called Nigger. Both progressive commentators, such as Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton, and the conservative-aligned news channel Fox News were outraged; Jackson called on entertainers to stop using the epithet after comedian Michael Richards used it onstage in late 2006.[56] Controversy escalated as the album's impending release date drew nearer, going as far as to spark rumors that Def Jam was planning to drop Nas unless he changed the title.[57] Additionally, then-Fort Greene, Brooklyn assemblyman (later United States Representative) Hakeem Jeffries requested that New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli withdraw $84,000,000 from the state pension fund that had been invested into Universal and its parent company, Vivendi, if the album's title was not changed.[58] On the opposite side of the spectrum, many of the most famous names in the entertainment industry supported Nas for using the racial epithet as the title of his full-length LP.[59][60] Nas's management worried the album would not be sold by chain stores such as Wal-Mart, thus limiting its distribution.[61]

On May 19, 2008, Nas decided to forgo an album title.[62] Responding to Jesse Jackson's remarks and use of the word "nigger", Nas called him "the biggest player hater", stating "His time is up. All you old niggas' time is up. We heard your voice, we saw your marching, we heard your sermons. We don't want to hear that shit no more. It's a new day. It's a new voice. I'm here now. We don't need Jesse; I'm here. I got this. We the voice now. It's no more Jesse. Sorry. Goodbye. You ain't helping nobody in the 'hood and that's the bottom line."[63] He also said of the album's title: "It's important to me that this album gets to the fans. It's been a long time coming. I want my fans to know that creatively and lyrically, they can expect the same content and the same messages. The people will always know what the real title of this album is and what to call it."[64]

The album was ultimately released on July 15, 2008, untitled. It featured production from Polow da Don, stic.man of Dead Prez, Sons of Light and J. Myers,[65] "Hero", the album's lead single released on June 23, 2008, reached No. 97 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 87 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles & Tracks.[66] In July, Nas attained a shoe deal with Fila.[67] In an interview with MTV News in July, Nas speculated that he might release two albums: one produced by DJ Premier and another by Dr. Dre—simultaneously the same day.[68] Nas worked on Dr. Dre's studio album Detox.[69] Nas was also awarded 'Emcee of the Year' in the HipHopDX 2008 Awards for his latest solo effort, the quality of his appearances on other albums and was described as having "become an artist who thrives off of reinvention and going against the system."[70]

2009–2012: Distant Relatives and Life Is Good

Nas and Damian Marley performing in Wellington, 2011 At the 2009 Grammy Awards, Nas confirmed he was collaborating on an album with reggae singer Damian Marley which was expected to be released in late 2009. Nas said of the collaboration in an interview "I was a big fan of his father and of course all the children, all the offspring, and Damian, I kind of looked at Damian as a rap guy. His stuff is not really singing, or if he does, it comes off more hard, like on some street shit. I always liked how reggae and hip-hop have always been intertwined and always kind of pushed each other, I always liked the connection. I'd worked with people before from the reggae world but when I worked with Damian, the whole workout was perfect".[71] A portion of the profit was planned to go towards building a school in Africa.[72] He went on to say that it was "too early to tell the title or anything like that".[73] The Los Angeles Times reported that the album would be titled Distant Relatives.[74] Nas also revealed that he would begin working on his tenth studio album following the release of Distant Relatives.[75] During late 2009, Nas used his live band Mulatto with music director Dustin Moore for concerts in Europe and Australia.[76]

After announcing a possible release in 2010,[77] a follow-up compilation to The Lost Tapes (2002) was delayed indefinitely due to issues between him and Def Jam.[78] His eleventh studio album, Life Is Good (2012) was produced primarily by Salaam Remi and No I.D, and released on July 13, 2012. Nas called the album a "magic moment" in his rap career.[79]

In 2011, Nas announced that he would release collaboration albums with Mobb Deep, Common, and a third with DJ Premier.[80][81][82] Common said of the project in a 2011 interview, "At some point, we will do that. We'd talked about it and we had a good idea to call it Nas.Com. That was actually going to be a mixtape at one point. But we decided that we should make it an album."[83] Life is Good would be nominated for Best Rap Album at the 2013 Grammy Awards.

2013–2019: Nasir and The Lost Tapes 2 In January 2013, Nas announced he had begun working on his twelfth studio album, which would be his final album for Def Jam.[84] The album was supposed to be released during 2015.[85] In October 2013, DJ Premier said that his collaboration album with Nas, would be released following his twelfth studio album.[86] In October 2013, Nas confirmed that a rumored song "Sinatra in the Sands" featuring Jay-Z, Justin Timberlake, and Timbaland would be featured on the album.[85]

On April 16, 2014, on the twentieth anniversary of Illmatic,[87] the documentary Nas: Time Is Illmatic was premiered which recounted circumstances leading up to Nas's debut album.[88] It was reported on September 10, that Nas has finished his last album with Def Jam.[89] On October 30, Nas released a song which might have been the first single on his new album, titled "The Season", produced by J Dilla.[90] Nas has also collaborated with the Australian hip-hop group, Bliss n Eso, in 2014. They released the track "I Am Somebody" in May 2014. Nas was featured on the song "We Are" from Justin Bieber's fourth studio album, Purpose, released in November 2015.

Nas performing at the 2015 Sugar Mountain festival in Melbourne Nas was announced as one of the executive producers of the Netflix original series, The Get Down, prior to its release in August 2016. He narrated the series and rapped as adult Ezekiel of 1996.

On October 16, 2016, he received the Jimmy Iovine Icon Award at 2016 REVOLT Music Conference for having a lasting impact and unique influence on music, numerous years in the rap business, his partnership with Hennessy, and Mass Appeal imprint by Puff Daddy.[91] In November 2016, Nas collaborated with Lin-Manuel Miranda, Dave East and Aloe Blacc on a song called "Wrote My Way Out", which appears on The Hamilton Mixtape. On April 12, 2017, Nas released the song Angel Dust as soundtrack for TV series The Getdown. It contains a sample of the Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson song Angel Dust.[citation needed]

In June 2017, Nas appeared in the award-winning 2017 documentary The American Epic Sessions directed by Bernard MacMahon, where he recorded live direct-to-disc on the restored first electrical sound recording system from the 1920s.[92] He performed "On the Road Again", a 1928 song by the Memphis Jug Band,[93] which The Hollywood Reporter describing his performance as "fantastic"[94] and the Financial Times praising his "superb cover of the Memphis Jug Band's "On the Road Again", exposing the hip-hop blueprint within the 1928 stomper."[95] "On the Road Again", and a performance of "One Mic",[96] were released on Music from The American Epic Sessions: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack on June 9, 2017.[97]

In April 2018, Kanye West announced on Twitter that Nas's twelfth studio album will be released on June 15, also serving as executive producer for the album.[98][99] The album was announced the day before release, titled Nasir.

Following the release of Nasir, Nas confirmed he would return to completing a previous album, including production from Swizz Beatz and RZA.[100][101][102] This project was released as The Lost Tapes 2 on July 19, 2019, which included production from Kanye West, Pharrell Williams, Swizz Beatz, The Alchemist, and RZA. This album was a sequel to Nas's 2002 release, The Lost Tapes.[103]

2020–present: King's Disease series, Magic series and DJ Premier collaborative album In August 2020, Nas announced that he would be releasing his 13th album. On August 13, he revealed the album's title, King's Disease. The album, executive-produced by Hit-Boy, was preceded by the lead single, "Ultra Black", a song detailing perseverance and pride "despite the system".[104] The album won the Grammy Award for Best Rap Album at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards, becoming Nas' first Grammy.[105] The sequel album, King's Disease II, was released on August 6, 2021,[106] and included the song "Nobody" featuring Lauryn Hill. King's Disease II debuted at number-three on the US Billboard 200, becoming Nas's highest-charting album since 2012.[107] On December 24, Nas released the album Magic. It is his third album executive produced by Hit-Boy, and includes guest appearances from ASAP Rocky and DJ Premier.[108]

Nas's third installment in the King's Disease series, King's Disease III, was released the following year. Like its two predecessors, King's Disease III was mainly produced by Hit-Boy; however, it was notably Nas's first studio album to forgo any guest appearances from outside artists.[109] Upon release, King's Disease III would become one of the most critically acclaimed albums of Nas's career, becoming his highest-scoring new studio album on review aggregator Metacritic and receiving critical praise for the cohesion of Hit-Boy's production with Nas's storytelling and lyricism.[110][111] Praising King's Disease III, British music publication NME stated that Nas, "three decades in, [is] still a force to be reckoned with", while Marcus Shorter of Consequence would write that the album was Nas's and Hit-Boy's "most focused and confident collaboration" and that Nas was "at peace with his legacy, life, and the fact that old age is inevitable".[112][111]

On September 12, 2023, Nas announced the 3rd installment to the Magic album series, Magic 3, which would be released two days later, on his fiftieth birthday.[113] The album would be the sixth and final collaboration between Nas and Hit-Boy on an album.[citation needed]

On April 19, 2024, it was announced for the 30th anniversary of Illmatic, that Nas and DJ Premier would be releasing their collaboration album in late 2024.[114]

Artistry Nas has been praised for his ability to create a "devastating match between lyrics and production" by journalist Peter Shapiro, as well as creating a "potent evocation of life on the street", and he has even been compared to Rakim for his lyrical technique. In his book Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop (2009), writer Adam Bradley states, "Nas is perhaps contemporary rap's greatest innovator in storytelling. His catalog includes songs narrated before birth ('Fetus') and after death ('Amongst Kings'), biographies ('UBR [Unauthorized Biography of Rakim]') and autobiographies ('Doo Rags'), allegorical tales ('Money Is My Bitch') and epistolary ones ('One Love'), he's rapped in the voice of a woman ('Sekou Story') and even of a gun ('I Gave You Power')."[115] Robert Christgau writes that "Nas has been transfiguring [gangsta rap] since Illmatic".[116] Kool Moe Dee notes that Nas has an "off-beat conversational flow" in his book There's a God on the Mic – he says: "before Nas, every MC focused on rhyming with a cadence that ultimately put the words that rhymed on beat with the snare drum. Nas created a style of rapping that was more conversational than ever before".[117]

OC of D.I.T.C. comments in the book How to Rap: "Nas did the song backwards ['Rewind']... that was a brilliant idea".[118] Also in How to Rap, 2Mex of The Visionaries describes Nas's flow as "effervescent",[119] Rah Digga says Nas's lyrics have "intricacy",[120] Bootie Brown of The Pharcyde explains that Nas does not always have to make words rhyme as he is "charismatic",[121] and Nas is also described as having a "densely packed"[122] flow, with compound rhymes that "run over from one beat into the next or even into another bar".[123]

About.com ranked him 1st on their list of the "50 Greatest MCs of All Time" in 2014, and a year later, Nas was featured on the "10 Best Rappers of All Time" list by Billboard. The Source ranked him No. 2 on their list of the Top 50 Lyricists of All Time.[124] In 2013, Nas was ranked fourth on MTV's "Hottest MCs in the Game" list.[125] His debut, Illmatic, is widely considered among the greatest hip hop albums of all time.[126][127]

Controversies and feuds 2Pac After 2Pac interpreted lines directed to the Notorious B.I.G. on Nas's 1996 album It Was Written to be aimed towards him, he attacked Nas on the track "Against All Odds" from The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory. Nas himself later admitted he was brought to tears when he heard the diss because he idolized 2Pac.[128] The two later met in Central Park before the 1996 MTV Video Music Awards and ended their feud, with 2Pac promising to remove any disses aimed at Nas from the official album release; however, 2Pac was shot four times in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada, three days later on September 7, dying of his wounds on September 13, before any edits to the album could be made.[129][130]

Jay-Z Initially friends, Nas and Jay-Z had met a number of times in the 1990s with no animosity between the two. Jay-Z requested that Nas appear on his 1996 album Reasonable Doubt on the track "Bring it On"; however, Nas never showed up to the studio and was not included on the album. In response to this, Jay-Z asked producer Ski Beatz to sample a line from Nas's song The World is Yours, with the sample featured heavily in what went on to be Dead Presidents II. The two traded subliminal responses for the next couple of years, until the beef was escalated further in 2001 after Jay-Z publicly addressed Nas at the Summer Jam, performing what would go on to be known as "Takeover", ending the performance by saying "ask Nas, he don't want it with Hov". After Jay-Z eventually released the song on his 2001 album The Blueprint, Nas responded with the song "Ether", from his album Stillmatic, with both fans and critics saying that the song had effectively saved Nas's career and marked his return to prominence, and almost unanimously agreeing Nas had won their feud. Jay-Z responded with a freestyle over the instrumental to Nas's "Got Ur Self a Gun", known as "Supa Ugly". In the song, Jay-Z makes reference to Nas's girlfriend and daughter, going into graphic detail about having an affair with his girlfriend.[131][132][133][134] Jay-Z's mother was personally disgusted by the song, and demanded he apologise to Nas and his family, which he did in December 2001 on Hot 97.[135] "Supa Ugly" marked the last direct diss song between Jay-Z and Nas, however, the two continued to trade subliminals on their subsequent releases. The feud was officially brought to an end in 2005, when Jay-Z and Nas performed on stage together in a surprise concert also featuring P. Diddy, Kanye West and Beanie Sigel.[136] The, following year, Nas signed with Def Jam Recordings, of which Jay-Z then served as president.[137]

Cam'ron After Nas was removed from the 2002 Summer Jam lineup due to allegedly planning to perform the song Ether while a mock lynching of a Jay-Z effigy took place behind him, Cam'ron was announced as a last minute replacement and headlined the show instead. Nas appeared on Power 105.1 days later and addressed a number of fellow artists, including Nelly, Noreaga and Cam'ron himself.[138] Nas praised Cam'ron as a good lyricist, but branded his album Come Home With Me as "wack".[139] After Cam'ron heard of Nas's words, he appeared on Funkmaster Flex's Hot 97 and performed a freestyle diss over the beat to Nas's "Hate Me Now", making reference to Nas's mother, baby mother and daughter. Nas did not respond directly but appeared on the radio days later, calling Cam'ron a "dummy" for supposedly being used by Hot 97 to generate ratings. Nas eventually responded on his 2002 album God's Son on the song "Zone Out", claiming Cam'ron had HIV. Cam'ron and the rest of T

- Pensacola: Wings of Gold – fictional television series set at NAS Pensacola

- List of United States Navy airfields

References

- ^ FAA Airport Form 5010 for NPA PDF

- ^ "Florida NPL/NPL Caliber Cleanup Site Summaries: Pensacola Naval Air Station 5 Year Progress Report". US Environmental Protection Agency. March 2003. Archived from the original on October 30, 2004.

- ^ "The Forts of Pensacola Bay" (history), Visit Florida Online, 2006, webpage: VFO-Forts.

- ^ "Fort San Carlos de Barrancas" (history), National Park Service (NPS), webpage: NPS-fort2.

- ^ a b Shettle, Jr., M. L., "United States Naval Air Stations of World War II, Volume I: Eastern States", Schaertel Publishing Co., Bowersville, Georgia, 1995, LCCN 94--68879, ISBN 0-9643388-0-7, p. 178.

- ^ Dibble, Ernest F., Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, Pensacola Series Commemorating the American Revolution Bicentennial 3, Pensacola, FL: Pensacola/Escambia Development Commission, 1974 p. 13.

- ^ Sharp, John G. Naval Surgeon Isaac Hulse re his patients at Naval Hospital Barrancas, 3 November 1828 http://genealogytrails.com/fla/escambia/1827navalhosp.html

- ^ Hulse, Thomas, Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), pp. 497–539.

- ^ Sharp John G. List of Mechanics, Laborers, &c employed in the Navy Yard Pensacola May 1829 http://genealogytrails.com/fla/escambia/pnyemployees1829.html

- ^ Dibble, p. 23.

- ^ Pensacola Gazette 6 April 1827, p. 5.

- ^ Sharp May 1829 List of Mechanics

- ^ Floridian and Advocate 10 September 1836 p. 1

- ^ Clavin, Matthew J. Aiming for Pensacola Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers, Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2015, p. 84.

- ^ Sharp, John G.M. Early Pensacola Navy Yard in Letters and Documents to the Secretary of the Navy and Board of Navy Commissioners 1826-1840, Part II,http://www.usgwarchives.net/va/portsmouth/shipyard/sharptoc/pensacola-sharp.html

- ^ Dibble, Ernest F. Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, p.72.

- ^ Ericson, David F. Slavery in the American Republic Developing the Federal Government, 1791 -1861 (University of Kansas Press:Lawrence Kansas 2011), 259n55.

- ^ Dibble, Ernest F. Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, p.67.

- ^ Hulse,Thomas Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), pp. 497–539.

- ^ Hulse, Thomas, "Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863," Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), 514 - 515.

- ^ Dibble, p. 62

- ^ Pearce, George F. The U.S. Navy in Pensacola From Sailing Ships to Naval Aviation (1825–1930) University of West Florida: Pensacola 1980 pp. 62–63.

- ^ Miller, J. Michael. "Marine's Telling of 1861 Florida Navy Yard Fall Given", Fortitudine, vol XX, no. 4 (Spring 1991): 8.

Bibliography

- FAA Airport Form 5010 for NPA PDF

- Clavin,Matthew J. Aiming for Pensacola Fugitive Slaves on the Atlantic and Southern Frontiers Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2015, p. 84.

- Dibble, Ernest F., Antebellum Pensacola and the Military Presence, Pensacola Series Commemorating the American Revolution Bicentennial 3, Pensacola, FL: Pensacola/Escambia Development Commission, 1974 p. 62

- Hulse, Thomas, Military Slave Rentals, the Construction of Army Fortifications, and the Navy Yard in Pensacola, Florida, 1824–1863, Florida Historical Quarterly, 88 (Spring 2010), pp. 497–539.

- Keillor, Maureen Smith, and Keillor, AMEC (SW/AW) Richard. Naval Air Station Pensacola. Arcadia Publishing, 13 January 2014. ISBN 9781467111010

- Pearce, George F. The U.S.Navy in Pensacola From Sailing Ships to Naval Aviation (1825–1930) University of West Florida: Pensacola 1980.

External links

- Official website

- List of Mechanics, Laborers, &c employed in the Navy Yard Pensacola, May 1829 (Genealogy Trails History Group)

- Pensacola Naval Hospital Records, November 1828 (Genealogy Trails History Group)

- Resources for this U.S. military airport:

- FAA airport information for NPA

- AirNav airport information for KNPA

- ASN accident history for NPA

- NOAA/NWS latest weather observations

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KNPA

- v

- t

- e

| Air Station |

|

|---|---|

| Station | |

| Outlying Field |

|

| Support Activity | |

| Other |

| Air Force Base | |

|---|---|

| Field | |

| Station |

|

| Range |

|

| Space Force Base | |

|---|---|

| Station |

| Army | |

|---|---|

| Air |

| Air Station | |

|---|---|

| Group |

|

| District |

|

| Prepositioning Site |

|---|